Synthetic lethality, an alluring genetic phenomenon, has sustained its captivating intrigue within scientific circles for decades. This concept, initially observed by American geneticist Calvin Bridges in fruit flies, involves the lethal outcome when specific non-allelic* genes combine, even though the homozygous parents were perfectly viable. The term “synthetic lethality”, which was later coined by Theodore Dobzhansky, denotes the combination of two entities to form something new. This new creation, however, is far from commonplace. It characterizes a unique genetic interaction where the co-occurrence of two genetic events results in organismal or cellular death. This interaction extends beyond loss-of-function mutations and includes various genetic changes like overexpression of genes, the action of a chemical compound, or environmental change.

Synthetic lethal (SL) genetic interactions arise as a consequence of cells and organisms employing intricate mechanisms to uphold homeostasis amid a spectrum of genetic and environmental complexities. Thus, robustness plays vital roles in evolution, developmental canalization, and complex diseases like cancer and can lead to SL interactions. Genetic robustness is demonstrated by the fact that despite many genes in budding yeast* being dispensable for growth in rich conditions, they become sensitive to additional perturbations such as knockout of a second gene or exposure to specific conditions. This powerful dynamic is established via various buffering mechanisms, such as functional redundancy and proteins known as capacitors. In diploid* organisms, having two alleles in the genome establishes redundancy, often making heterozygous knockout mice* indistinguishable from their wild-type counterparts. Another form of redundancy involves genes with shared ancestry that can partially perform the same function. Robustness is mostly provided by non-homologous genes operating in the same cellular process or in back-up pathways. For instance, a large scale RNA interference (RNAi) screen identified human genes as synthetically lethal with low paclitaxel concentrations, including mitotic spindle proteins and proteasome components, indicating that mitosis is buffered at several different levels. Capacitors like heat shock proteins and chromatin regulators provide additional buffering against mutations, resulting in multiple SL interactions. Capacitors may also explain the effectiveness of HSP90 and histone deacetylase inhibitors as anticancer drugs.

The full potential of synthetic lethality has been most extensively observed in yeast. Genome-wide quantitative mapping of SL interactions produces extensive genetic networks, which are valuable for gene functional annotation. SL interactions with genes are also apparent within drug contexts, enabling the examination of drug impacts on cells. It is known that drug-gene interaction screens in yeast have been extensively used to examine the effects of drugs.

Synthetic lethality in the context of cancer

Knowledge of drug-gene SL interactions could aid in designing combination therapies and predicting synergistic/sensitizer drugs, particularly in the context of cancer. Understanding why specific cancer cells respond to certain chemotherapy while others resist remains largely unclear. The effectiveness of drugs like Bortezomib, Vorinostat, and Geldanamycin in certain cancers may stem from synthetic lethality, despite these drugs not directly targeting tumorigenesis. For instance, given some of the hallmarks of cancer such as genomic instability, defective DNA repair, and deregulated transcription, drugs perturbing these processes may be synthetically lethal in cancer cells. On the other hand, the discovery of novel SL interactions in specific cancers, particularly the mapping of interactions between DNA repair pathways and DNA damage-based therapies, is believed to significantly enhance treatment decision-making. While a multitude of molecular aberrations are evident in cancer, the seamless translation of this knowledge into efficacious therapeutic interventions remains a formidable challenge. A major hurdle in drug discovery is that most oncogenes are not easily accessible for inhibition by small molecules and the restoration of loss-of-function changes in tumor suppressor genes in patients is nearly impossible. SL presents a promising prospect for addressing this intricate scenario. Given the distinctive molecular changes exhibited by cancer cells in comparison to their wild-type* counterparts, there is a lot of potential for SL partners of cancer-associated alterations to present viable therapeutic avenues.

A landmark achievement pertaining to the potential of SL-based cancer therapy is the tumor suppressor and DNA repair genes BRCA1 and BRCA2, mutations in which can cause breast and ovarian cancer. The BRCA genes display synthetic lethality with another DNA repair enzyme called PARP and the tumors of patients carrying these mutations could be successfully treated using a chemical PARP inhibitor with remarkably mild side effects. The BRCA-PARP SL interaction results in BRCA mutant cells displaying significantly higher sensitivity to PARP inhibitors compared to non-mutant cells. This pronounced responsiveness likely underpins its clinical effectiveness. Notably, recent research has proposed several additional SL counterparts of PARP, among them the tumor suppressor PTEN.

Synthetic lethality screen

The two primary approaches in classical genetics can also be applied to categorize SL screens* in human cells. The first approach is that traditional forward genetics starts with a phenotype of interest, for instance, obtained by screening a collection of mutants, and aims to identify the responsible gene. This strategy uses the genetic variability in a collection of cancer cell lines. Conversely, the second approach, known as reverse genetics, involves studying defined mutants, such as knockout mice, to uncover the functional consequences of these genetic changes. In this strategy, a single specific genetic change is engineered, resulting in an isogenic cell line pair*. In both scenarios, the subsequent phase involves identifying essential genes for cell viability through RNAi-mediated knockdown and linking these to the genotypic distinctions. However, a thorough examination of the strengths and weaknesses of both approaches has been the subject of ongoing discussion.

To date, several RNAi screening approaches have been used to identify SL interactions with oncogenic RAS*. Directly targeting RAS with small molecule inhibitors proves challenging, thus rendering synthetic lethality an appealing avenue for therapeutic intervention. These studies also contribute to a comprehensive understanding of the various screening methodologies currently available. In addition, they provide a platform for in-depth exploration of the present constraints and complexities inherent in conducting synthetic lethality screens in human cells.

In conclusion, the concept of synthetic lethality proves to be an invaluable lens through which to illuminate gene functions, drug mechanisms, interactions, and notably, cancer therapy.

*Glossary

(Arranged alphabetically )

Budding yeast: The budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a powerful model organism for studying fundamental aspects of eukaryotic cell biology [4].

Diploid: Two sets of chromosomes (2N) [1]. In human: 2N = 46

Haploid: One set of chromosomes (N) [1]. In human: N = 23

Isogenic cell line pair: Isogenic pairs of cell lines, which differ by a single genetic modification, are powerful tools for understanding gene function [3].

Knockout mouse: A knockout mouse is a laboratory mouse in which researchers have inactivated, or “knocked out,” an existing gene by replacing it or disrupting it with an artificial piece of DNA. For further details, refer here.

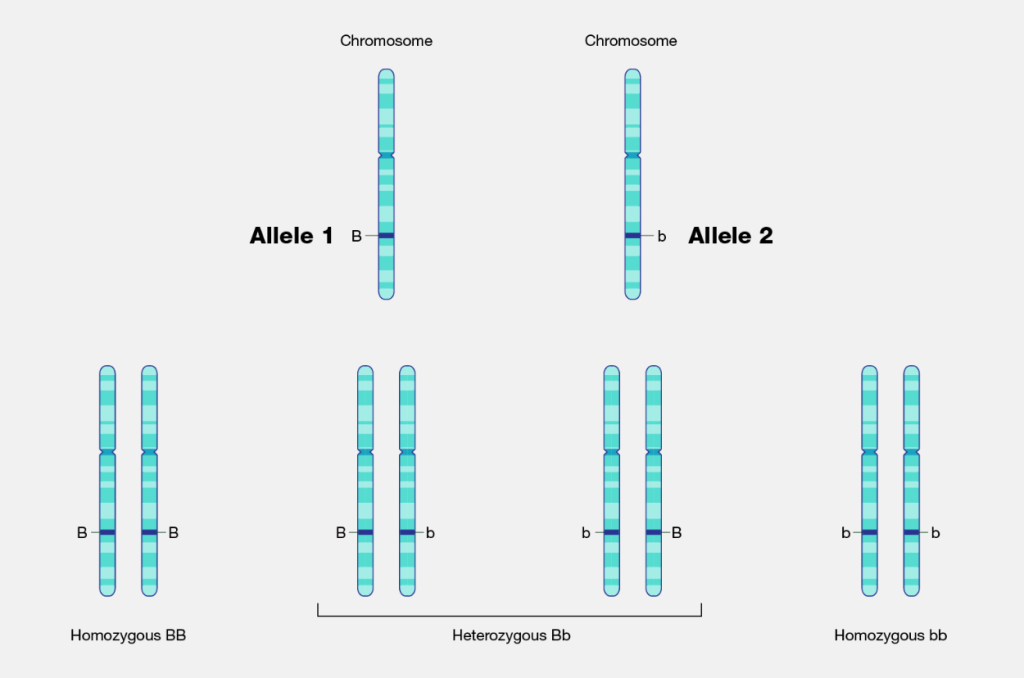

Non-allelic: An allele (originally allelomorph) is a form of variant (sometimes called a mutation) of a gene [1]. If the alleles are located at different loci on the homologous chromosome, they are referred to as non-allelic genes. (see Figure 1)

RAS: A third of all human cancers, including a high percentage of pancreatic, lung, and colorectal cancers, are driven by mutations in RAS genes. When RAS genes are mutated, cells grow uncontrollably and evade death signals. For further details, refer here.

SL screen: The synthetic lethal screen is a method of isolating novel mutants whose survival is dependent on a gene of interest [2].

Wild-type: In genetics, the wild-type organisms serve as the original parent strain before a deliberate mutation is introduced (for research) so that geneticists can use them as reference to compare the naturally occurring genotypes and phenotypes of a given species against those of the deliberately mutated counterparts.

Should any revisions be necessary, please feel free to contact me using the information provided on the Contact page.

References

[1] Berry, R. J. 2001. Phenotype, a Historical Perspective. Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, 1–8. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-384719-5.00107-6

[2] Barbour, L., Xiao, W. 2006. Synthetic lethal screen. Methods Mol Biol. 313:161-9. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-958-3:161. PMID: 16118433.

[3] DeWeirdt, P.C., Sangree, A.K. 2020. Hanna, R.E. et al. Genetic screens in isogenic mammalian cell lines without single cell cloning. Nat Commun. 11, 752.

[4] Duina, A.A., Miller, M.E., Keeney, J.B. 2014. Budding yeast for budding geneticists: a primer on the Saccharomyces cerevisiae model system. Genetics. 197(1):33-48. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.163188. PMID: 24807111; PMCID: PMC4012490.

Leave a comment